- Home

- Steve Bartholomew

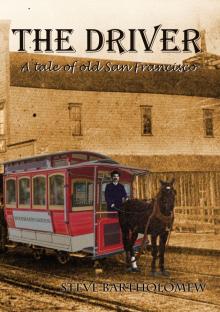

The Driver

The Driver Read online

The Driver

Steve Bartholomew

Dark Gopher Books

The Driver, © 2019 by Steve Bartholomew, published 2019 by Dark Gopher Books. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photo copying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system now known or hereafter invented without express written permission. Magazines, E-zines and other journalists are welcome to use excerpts from the book in their articles and stories.

Cover art by Crystalwizard.

This is a work of fiction. All characters are fictitious and do not represent real persons living or dead.

Created with Vellum

Contents

1. The Murder

2. The Coppers

3. Sunday

4. Laughing Larry

5. News

6. Funeral

7. Riot

8. More Questions

9. Inquest

10. Jail

11. Hiding Out

12. Thaddeus

13. Dragon’s Tooth

14. Fox

15. In the Cell

16. The Dagger

17. Hatchet Men

18. Genevieve

19. A Book of Maps

20. Indictment

21. Deposition of Genevieve Sutliff

22. Confession

23. Prison

Other books by Steve Bartholomew:

1

The Murder

San Francisco, 1877

Georg Vintner reined in his horse when he caught sight of the riot ahead. His horse, Jim, stopped and hung his head, probably grateful for a moment of unexpected rest. Georg merely stood still and watching. At first he didn’t realize what he was looking at. There should be no crowd there, in the middle of the street, in the middle of a foggy cold day.

“Why are we stopping? This is not a regular car stop.” It was one of the passengers, speaking from behind him. Georg glanced back. He saw a short, stout fellow in business man’s dress, tailed coat and top hat.

“See for yourself. I’m not driving into the middle of that mob. They look unruly.”

“I have an important appointment with my broker. I could lose money if I’m late.”

Another man came forward. “You could lose more than that, mate, you get mixed up in that bunch.” He spoke with an Aussie accent. “That there’s your Workingman’s Party. Scalawags and ruffians all.”

The business man cleared his throat. “I see. That would be Mr. Denis Kearney’s group then. Yes, I should like to avoid them.”

“How do you know it’s them?” Georg asked. “I have heard of them. This is the first I’ve run into any.”

The second fellow wore a working man’s dress himself, canvas shirt and pants with a vest but no tie. An old derby hat. “Don’t you see that sign they’re waving around? Chinese must go! That’s their whole platform. Kearney don’t care about working men, he just wants to get fellows riled so they’ll donate and vote for him. Low class, he is. I’m a union man myself, but I’ve no use for his sort.”

The business man nodded. “I don’t usually agree with your unions, but I’ll make an exception here. Speaking as a capitalist, I think you are right.”

“Hah. Me, I’m thinking I’ll depart this fine street car and find another way around. Good day to you, sir, and Driver.” The working man jumped out into the street and walked away.

“What do you think?” Business Man touched Georg’s shoulder. “Should I remain or evacuate?”

Georg shrugged. “Suit yourself, sir. You’re probably safe enough on my car as long as that mob doesn’t move in this direction. Me, I’ll see to my horse.”

He set the brake and dismounted from his perch. Grabbing a canvas bucket from the tool box, he filled it with water from the keg slung below the undercarriage. Then he walked around to water Jim and talk to him. It’s all right, fellow, just a short stop. We’ll be on our way again.

“Any trouble with your beast?” A woman’s voice. Georg looked around to see a lady about his own age, maybe forty, well dressed but not flashy, a long brown dress and hat covering dark brown hair. Not one of the fancy women from the parlor houses. Prosperous but not rich enough for her own horse and carriage. She was probably some kind of shopkeeper.

“Jim is fine,” Georg said. “A little annoyed maybe. This is the end of his shift, he’s looking forward to the barn. We can only work a street car horse four or five hours without a break. As it is, they only last about four years before they break down. I try to treat them nice, never whip ‘em.”

She nodded, looking him up and down. She reached to give Jim a scratch behind the ears. “What about you? How often do you get a rest?”

He laughed. There was something about her that made him laugh. Maybe just the way she looked at him, with open curiosity. “Us drivers don’t rest as much as the horse. I work sixteen hours, six days a week. “Course, I do get a break now and then when we’re changing livestock.”

“I remember now. There was a bill to reduce your work hours to twelve, but it was turned down.”

“Yes ma’am, but I’m glad to have a job.”

Most of the other passengers by now had left the car. It could carry twenty, but today there had been only eight or nine. Most of them were standing around on the sidewalk, viewing the mob up ahead. A few had already walked away. This car had no rear exit, so they had all gone past the Driver on their way out. Most rail cars had a separate door in back, but that meant hiring a second man as conductor. This railway was trying the experiment of running with only one man. He might miss a few fares, but it was still cheaper than paying two salaries.

“Looks like trouble,” someone said.

Georg looked up. From somewhere came the sound of a shrill whistle, followed by renewed shouts and a few screams.

“Here comes the militia,” the woman said.

Now Georg could see men on horseback, charging into the mass of rioters. The whole mob began running downhill, in Georg’s direction. By instinct he grabbed Jim’s reins to keep him from bolting.

He said to the woman, “Perhaps you should get back on the car, ma’am. Someone may get hurt.”

She gave a sniff. “You needn’t call me ma’am. I am Mrs. Genevieve Sutliff. I shall stand my ground.” She raised a small parasol, which Georg hadn’t noticed. She held it like a pistol. The other passengers by now had already scattered.

“I’m pleased to meet you, Mrs. Sutliff. I’m Georg Vintner.”

In a moment the mob was upon them, screaming and shouting men, mostly in their shirtsleeves, many carrying axe handles. Ten or twelve militia men pursued them on horse, wielding swords.

A large man, still wearing his derby, confronted Georg. “You look to me like one of them Chinee lovers!”

Jim the horse whinnied and tried to rear. Georg didn’t want to let go of the reins. He glanced at the man’s axe handle. “You look to me like a stupid oaf.”

At that the fellow drew back his weapon, preparing to strike. He didn’t get the chance. Genevieve Sutliff stepped forward. “I’m Chinese myself. Don’t you love me?” And with that she shoved her parasol into the man’s left eye. He screamed, dropped his club, and ran.

Georg gave her a sideways glance. She didn’t look Chinese.

In a few minutes the riot was over, the horsemen pursuing the few hold-outs down several streets. Georg turned to look at Genevieve. She smiled.

“That man may lose an eye.”

“I’m terribly sorry. I shall apologize when I see him again.” She still smiled.

He looked around. A few of the mob had been lying in the street, but they got up one by one and wandered off. “Well, I must say that was interestin

g. You have gained my respect, Mrs. Sutliff. From now on you may ride for free on my streetcar. Shall we get on board?”

“Indeed.” She allowed him to take her arm and help her mount the step. He said, “I guess now you’re my only passenger.”

She looked toward the back of the car. There were two long benches, one on each side. At the very back a well-dressed man was slumped over, apparently asleep. Genevieve said, “There’s one more. I wonder he could sleep through this.” She walked back to him and bent over him a moment. Then she straightened and gave Georg a strained look.

“You had better see.”

Georg followed her back and got a closer look. It was a young man with a well-trimmed beard, dressed in expensive clothes. He did seem asleep. For a moment Georg saw nothing amiss. Then Genevieve pointed to his ornate embroidered vest.

“Oh, I do see.” In his first glance he had not noticed it, with all the fancy silver embroidery and beadwork. The hilt of a small dagger stuck out from just below where the man’s heart would be.

Georg said, “I’ll put up the Out of Service sign.”

2

The Coppers

He had to wait nearly an hour before the coppers would talk to him. He'd made it back to the horse barn on Valencia Street without encountering any more rioters. Mrs. Sutliff had insisted on riding along, though he'd advised her not to. "You don't need to get involved in this," he told her. "It's my streetcar."

"I'm a witness," she said. "I have nothing to fear. But I don't want those lawmen trying to blame this on you just so they can say they made an arrest."

So a cop showed up at the barn. He looked over Georg's car and the body. Then he sent a runner to City Hall, and the police wagon came to escort everyone including the dead fellow to Headquarters. Once there, Georg and Miss Sutliff were left sitting for three quarters of an hour before a police captain in uniform came for the lady. They interviewed her first while Georg waited.

He fumed in silence. He was losing time from work. He was losing money. He hoped this wasn't going to get him fired. He liked the job and didn't feel like finding another one just yet.

Genevieve Sutliff came back from the interview room, followed by the captain. She paused to hand him a small card. "Here's my pasteboard. You come and see me, if you wish." The card said, SUTLIFF FINE PRINTING with an address on Montgomery Street. He had to spell out the words, moving his lips.

"No talking to other witness, ma'am," the captain said. He ushered her out the door, then left Georg sitting another twenty minutes.

Finally a patrolman came out and pointed at Georg. "You next." He jerked a thumb toward the interview room.

The room was small, with a rolltop desk in one corner and a table and three chairs in the middle. It reeked of stale cigar smoke. The captain and another man, in civilian suit, were sitting at one side of the table. The patrolman behind Georg shoved him into the other chair, then left the room.

The civilian looked to be forty or fifty, full mustache, slightly threadbare but expensive suit. Georg felt he had seen the man before somewhere, maybe around City Hall at some civic function such as a parade or ribbon-cutting.

"Mr. Vintner," the man said when Georg was seated. "Have I got your name right? What kind of name is that, by the way? German?"

"Norwegian."

"I see. Well, my name is Cyrus Potter, Commissioner of Police. You have already met Captain Murphy. Been in this country long, have you?"

"Long enough. I came over when I was six, with my pa."

"Uh huh. You belong to the Workingman's Party, Mr. Vintner?"

"No, why would I?"

"Well, the party advocates a eight hour work day. How do you feel about that?"

"Great idea. I don't like most of their other ideas."

Captain Murphy was taking notes on a yellow pad. He scratched something down in pencil. Georg made an effort not to glance at what he was writing. The Commissioner said, "Did you know the deceased? He was murdered on your car in the midst of a riot. Tell us what you saw."

Georg shrugged. "I don't know the man. I didn’t see who gutted him because I was busy watching a riot. I didn't even know he was dead until Mrs. Sutliff pointed him out."

Potter glanced at Murphy. "The deceased is Alexander Penworthy. He belongs to the Penworthy lumber and milling family. If he hadn't been stabbed he might have inherited a few million when his father dies. Now I don't know who gets the money. I guess you can go back to work now, Vintner. Just don't leave town."

As Georg was getting up, the Commissioner said, "By the way. The Penworthys own a lot of stock in your rail company. I wonder who might have had a grudge against Alexander?"

Georg looked him in the eye. "I need a ride back to the horse barn."

By the time he got back to work he had only three hours left in his shift, enough time for a round trip to Sutter and Market Street, his normal route. Of course he would lose pay for the time he’d wasted at the Police station. He saw no point in complaining. He got back to his rooming house by midnight, ate a bowl of soup kept warm for him by Mrs. Costello, then fell into bed. He pulled off his boots but didn’t bother about his clothes. They still looked clean enough for another day or two.

In the morning, after six hours of deep sleep, he wolfed down a breakfast of pancakes and bacon, then returned to work. That was Saturday. He got to the barn and signed out his car. The foreman, Bob Mullins, gave him a strange look.

“You seen the Morning Call yet?”

“I don’t read the papers,” Georg said. The truth was he had trouble reading at all, but usually didn’t admit it.

“You’re mentioned.” Mullins waved the paper in his face. “You were in that riot yesterday. It says here you witnessed a murder. Some rich toff.”

“I didn’t witness anything. I just happened to be there.”

Mullins said no more. He still had a strange look. Georg mounted his car and snapped the reins, moving off.

The rest of the day was a routine Saturday, except for one odd event. His passengers were the usual mix of capitalists, working men and layabouts, rich, poor, and middling. Mostly men, a few women and children. Someone always rose to give a lady a seat. Then, half way through the trip, Genevieve Sutliff boarded. After dropping her fare in the box she leaned over the partition that separated the driver from the car.

“Come and see me tomorrow. You have my address.”

Georg glanced around in some astonishment. This was not how proper ladies behaved. Before he could respond she had moved toward the back of the car.

“Yes ma’am,” he muttered to his horse. Her words had sounded like a command.

3

Sunday

Sunday morning he slept late, till around six a.m. The Driver had enough seniority with the company to get Sundays off. He would have preferred a different day since most businesses were closed on Sunday. But Mullins said it was company policy. The fact was most drivers didn’t stay long enough to get seniority.

The night before, he had enjoyed his weekly hot bath provided by the nearby bath house. He had therefore slept in a nightshirt instead of his uniform. This morning he dressed in his good suit, well brushed by Mrs. Costello. Usually he wore it only on the rare occasions he attended church. Today he felt he ought to be formal.

After breakfast he went for a walk through Portsmouth Square, enjoying the unusual sunshine. Most mornings had fog this time of year, though it heated up in the afternoon. He noticed the water out in the bay. It looked choppy, with whitecaps. Wind sailors coming from the sea would have work to do.

In the afternoon he sat for awhile listening to a brass band playing Rock of Ages. Then he gathered his courage and walked across town to the address on the pasteboard.

SUTLIFF FINE PRINTING was a small shop located in an alleyway off Montgomery Street. This being Sunday, there was a Closed sign in the window, but he pulled the bell cord anyway.

She opened almost at once, after peeking at him through a loophole. She glance

d up and down the street, as if to check whether he was being followed. She wore a plain dress with apron.

“I’m glad you came,” she said. “I was worried you might decide to stay away.”

He adjusted his coat and tie, glancing around. “This is a nice shop. It appears well-ordered, ship-shape.” The smell of ink and other chemicals were like a strange incense.

She looked pleased. “Thank you. It’s a great deal of work, of course. Here, some examples of my product.” She handed him a few ornately engraved greeting cards. He could make out Happy Birthday on one, though the flowing script at first baffled him. Georg didn’t read much, but he could recognize some words.

“The press is in back,” she said. “Of course it’s hand operated, not by steam. I hire a Chinese man to run it. He’s very good. Did you know the Chinese invented printing? I don’t know what we should do without them. And that Mr. Kearney wants to kick them out.”

He asked permission and then took a seat by the counter. When working, he spent sixteen hours a day standing behind his horse. It was always good to sit down.

“Mrs. Sutliff, may I ask what you wanted to see me about?”

She leaned against the counter rather than sit. “First, may I offer you something? I have tea brewing. Or a bit of wine perhaps?”

“No thanks, ma’am, I don’t often drink anymore.”

“I see. Well then.” She cleared her throat, perhaps unsure how to begin.

“Two men came to see me yesterday morning. Detectives.”

He shrugged, waiting. After a moment she went on.

“They’re trying to figure out who to pin that murder on. There’s going to be more about it in the papers. The Penworthys are an important family in this town. The Police will want to hang someone.”

“And what could you tell them they didn’t already know?”

She pulled open a drawer and handed him a sheet of paper. It was blank except for some printing at the top.

The Driver

The Driver